“There are costs to the status quo”: the role of data in building gender-fit practices

This blog includes and expands on the brief Equality Insights presentation at OECD GenderNet 2020.

2020 has been a devastating year on so many fronts, including for gender equality. In May 2020 the UNDP Human Development Report Office issued a statement saying that for the first time since 1990 global human development could decline. As a result of COVID more women have lost jobs, care loads have increased, violence in homes has increased. Hard fought gender equality gains are being lost. The UN Secretary General has been saying that COVID has already ‘reversed decades of limited and fragile progress on gender equality and women’s rights.’ .

The need for a strong, coordinated, shared and well-resourced gender equality agenda has never been greater.

So, how can we galvinse action for gender equality in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, and be effective and “fit” for gender equality in development policy and practice?

This was the overall theme at the annual meeting of the OECD GenderNet in early October. The Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Network on Gender Equality, is a subsidiary body of the OECD DAC and provides a platform for gender experts from development co-operation agencies to meet and define common approaches. Gender specialists and advocates from a range of civil society organisations attend as observers, sometimes also contributing expertise as presenters.

A virtual GenderNet

Like most meetings this year, the 2020 GenderNet was held virtually and even had sessions in different time zones –offering a rare opportunity for Australians to engage in a global forum at a decent hour!

The meeting aimed to share innovative and transformative approaches, coping mechanisms, and new ways of working, consider improvements in institutional practices based on learning to date, and build collective action.

The Equality Insights team had the opportunity to make brief remarks about gender-fit data as a foundation for gender-fit policy and practice. Remarks (edited for clarity) are shared here:

Data is vital to being gender fit

In the first week of October, the World Bank released its assessment that in 2020, COVID-19 will push as many as 150 million people into extreme poverty by 2021.

Routine poverty measurement should be able to tell us how many of these people are women, of what age, ability, sociocultural background etc. It can’t.

Gender-blind approaches to poverty measurement are a legacy of longstanding gender inequalities. While they persist, they slow action, making intersectional gender inequality and its impacts harder to see, and to tackle. That they persist, is very much within our ability to change.

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action called on national and international statistical organisations to ‘collect gender and age-disaggregated data on poverty’ and ‘examine the relationship of women’s unremunerated work to the incidence of and their vulnerability to poverty’.

25 years later household-level poverty data continues to provide the basis for estimating poverty and inequality.

One reason that gender-blind poverty measurement has persisted has been lack of an alternative.

12 years ago, with support from the Australian Government, a group of civil society organisations and research institutions, including International Women’s Development Agency, and the Australian National University, set out to develop a credible alternative

The Individual Deprivation Measure, which IWDA is taking forward as its flagship program, Equality Insights, collects individual-level, gender-sensitive data on 15 dimensions of life and assets, including dimensions that are particularly relevant for gender equality and women’s empowerment, such as time use, paid and unpaid work, and voice. Because it collects information about multiple dimensions from a single individual, it can show how dimensions are inter-related. All adults in a sampled household are surveyed, to provide insights into disparity within households.

Why does this matter?

In early 2020, IWDA undertook data collection in the Solomon Islands.

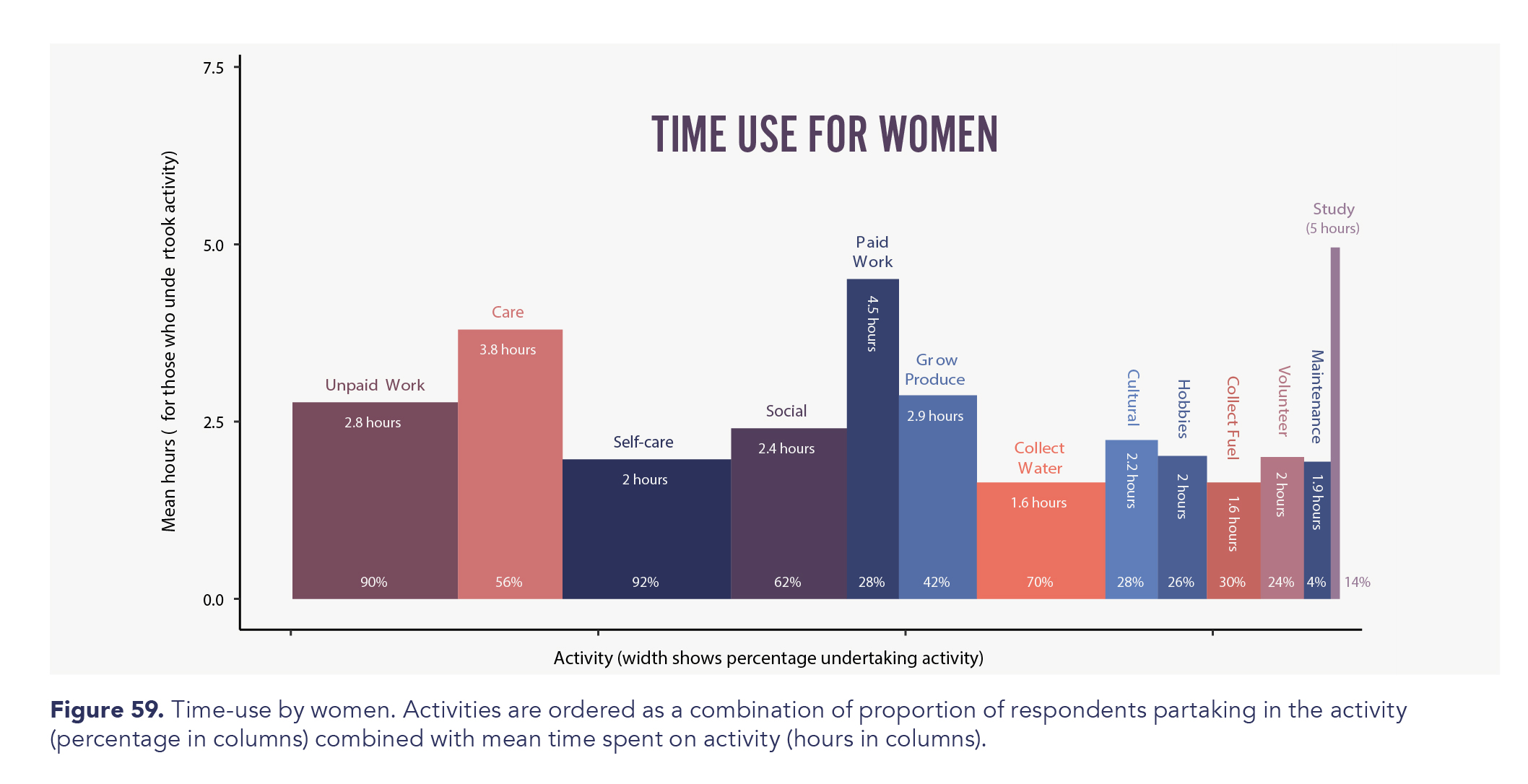

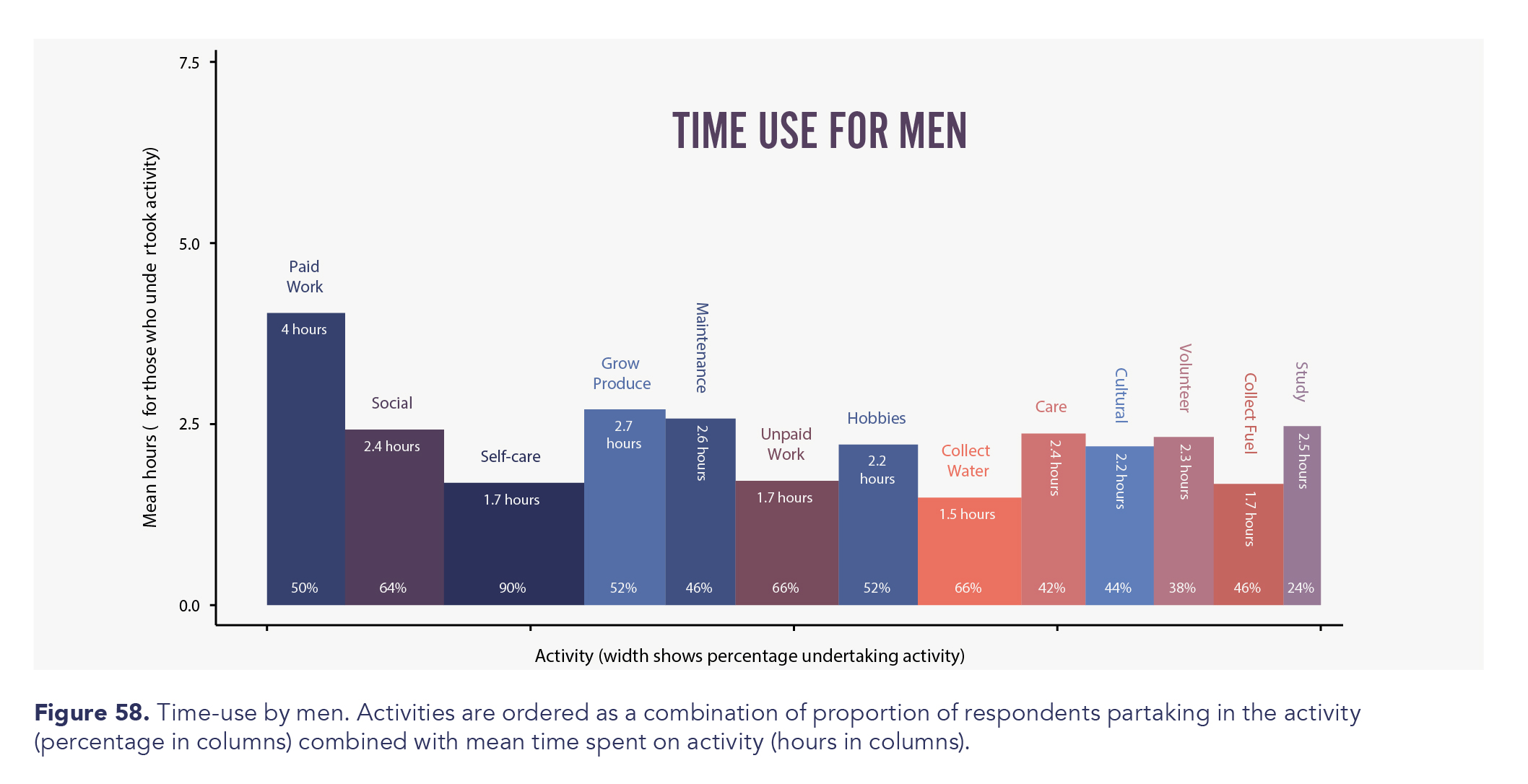

Data from the time-use dimension showed that the primary activities for women were unpaid work, followed by care work, and women were far more likely than men to have a child or other dependent in their care while they are doing activities. The primary activities for men were paid work, followed by socializing.

In the voice dimension data showed that more men than women had sole decision making power over household finances, large purchases, duration of their work, and social commitments.

In the work dimension, data showed the impact of gendered norms:

- On average, women spent 2 more hours on unpaid domestic work and care than men

- Women without paid work did more unpaid domestic work than women with paid work (40 minutes more)

- However, men without paid work did virtually no more unpaid domestic work than men with paid work (only 6 additional minutes)

Regarding assets, men were more likely than women to own:

- Transport-related assets, with implications for time-use;

- Assets relevant to participating in business, and for accessing information.

- The only asset owned by more women than men was a sewing machine.

Policy insights from just these four dimensions are clear: women’s participation in paid work requires addressing their responsibilities for unpaid care. Ensuring paid work contributes to wider empowerment means responding to unequal decision-making power between men and women –generally, and within the household. Investing in community and tertiary infrastructure can contribute to economic pathways to women’s empowerment if it helps overcome the asset gap.

There is power in having inclusive, intersectional, gender-sensitive, quantitative information from a single survey that can inform targeted action on poverty and inequality.

Accelerating change

Shifting standards about what constitutes adequate data is part of building ‘fitness’ for gender equality work. OECD GenderNet can play a role in setting standards, and help shift resources away from ‘gender blind by design’ data, to gender-fit data.

There are costs to the status quo, not just to change.

We think the mandate and position of GenderNet make it well placed to examine the costs of data that makes it harder to see the lives of diverse women.

We commend the Australian Government for their investment in creating an alternative.

Comments